Decision making is a pretty crucial skill. It can also be fiendishly difficult.

Our brains, after all, are amazing in their complexity. But they can also trip us into foolish behaviour.

What do we do when faced with a difficult decision? In 1772, Benjamin Franklin recommended a process of comparing ‘pros and cons’ when faced with a tough decision. It’s the process that most of us still use today.

But according to Chip and Dan Heath in their book Decisive, it’s profoundly flawed. The reason? It fails to recognise the biases that commonly affect our thinking, in particular:

- Narrow framing: rather than recognising that there are almost always several options, we tend to frame decisions as a choice between two options. Should we do this or that?

- Confirmation bias: our brains like to unconsciously make quick gut decisions, then look for evidence that confirms their initial view. So pros and cons lists that may seem objective to us, are often inherently biased.

- Short-term emotion: when we have a tough decision to make, emotion can cloud our thought process. Instead of the clarity we need, we constantly ruminate on the issues, making an effective decision even harder.

- Overconfidence: we place too much confidence in the information we have close to hand, and fail to consider what the future may hold. After all, we don’t know what we don’t know.

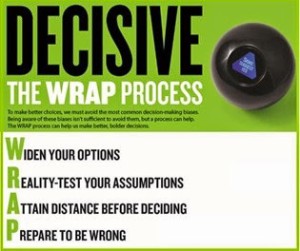

To combat these biases, the Heath Brothers created the WRAP process to facilitate better decisions. And there’s a great movie proponent of it too: Henry Fonda’s Juror 8 in 12 Angry Men. Here’s how he models each part of the WRAP approach.

Widen your Options

As we have a tendency towards narrow framing, we need to consciously widen the options we consider.

In 12 Angry Men, the majority of jurors think the defendant is guilty based on the evidence presented. Juror 8 urges them to widen the options: to consider not just whether the defendant is guilty based on the evidence, but whether the evidence itself is credible. Or are there other interpretations of the evidence than those provided by the prosecution?

Reality-test your assumptions

Confirmation bias leads us to prioritise information that confirms our unconscious initial decision. In 12 Angry Men, the majority of jurors are biased by the defendant’s background, or by their own prejudices. Consequently, they easily lap up the prosecution’s case.

Juror 8 challenges those assumptions through his own experiments. He tests the prosecution’s assertion that the murder weapon is almost unique by finding an identical knife in a pawnshop a few blocks away. And in the scene below, he stages a recreation of a witness testimony which suggests it’s deeply flawed.

Other jurors lend their personal experiences to reality-test the evidence. The lonely elderly juror, the man who lived near the elevated subway, and the juror who’d witnessed other knife fights all use personal experience to cast doubt on the defendant’s guilt.

Attain distance before deciding

This is Juror 8’s initial gambit. When they retire to make their decision, all the other jurors are unanimous in their belief that the defendant is guilty. It’s a hot, sticky day, and they want a quick decision so they can get back to their lives.

But on their initial vote, Juror 8 votes not guilty. He’s not sure either way: he just wants to force his fellow jurors to look at the case critically. And in the scene below, he gains a supporter: Juror 9 is also not convinced either way, but gives Juror 8 his backing in creating some distance before deciding.

Prepare to be wrong

Most of the jurors suffer from overconfidence, a belief that their way of interpreting the evidence is foolproof. But this overconfidence is gradually picked apart under Juror 8’s persistence. One key witness is revealed to be short-sighted, another appears to be embellishing his story for attention.

And of course, the actual guilt of the defendant in 12 Angry Men is left ambiguous. As we rarely have all possible information, the Heath Brothers advise us to prepare for bad outcomes as well as good ones.

This thought is clearly in the mind of one juror when he taunts Juror 8 with the possibility that he’ll have let a guilty man go free. But by going through the elements of the WRAP approach, Juror 8 can at least be confident that they’ll have made an informed rather than a biased decision, and succeeded in casting reasonable doubt on the guilt of the defendant.

You can find out more about the WRAP process, including some additional tools, at www.heathbrothers.com